Tag: Green Issues

Prospectors hit the gas in the hunt for ‘white hydrogen’

For more than a decade, the village of Bourakébougou in western Mali has been powered by a clean energy phenomenon that may soon sweep the globe.

The story begins with a cigarette. In 1987, a failed attempt to drill for water released a stream of odourless gas that one unlucky smoker discovered to be highly flammable. The well was quickly plugged and forgotten. But almost 20 years later, drillers on the hunt for fossil fuels confirmed the accidental discovery: hundreds of feet below the arid earth of west Africa lies an abundance of naturally occurring, or “white”, hydrogen.

Today, it is used to generate green electricity for Bourakébougou’s homes and shops. But geologists believe that untapped reservoirs of white hydrogen in the US, Australia and parts of Europe have the potential to provide the world with clean energy on a far greater scale.

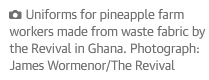

‘We turn waste into something golden’: the creatives transforming rags to riches

Rich nations’ unwanted clothes often end up in landfills, polluting the global south. But entrepreneurs in Ghana, Pakistan and Chile are turning rubbish into rugs, shoes and toys

Every second, the equivalent of a lorry full of clothes ends up on a landfill site somewhere around the world. People are buying, and casting off, more clothes than ever. On average, each consumer buys 60% more clothing than 15 years ago and 92m tonnes of textile waste are created annually.

Production and consumption are on the rise, with severe environmental and social implications. Only 12% of the material used for clothing is recycled. A popular way to dispose of clothes is to give them to charity shops.

But many of these donations end up in countries in the global south, where there is big trade in second hand clothing.

Prospectors hit the gas in the hunt for ‘white hydrogen’

The zero-emission fuel may exist in abundant reserves below ground. Now large sums are being invested to look for it

For more than a decade, the village of Bourakébougou in western Mali has been powered by a clean energy phenomenon that may soon sweep the globe.

The story begins with a cigarette. In 1987, a failed attempt to drill for water released a stream of odourless gas that one unlucky smoker discovered to be highly flammable. The well was quickly plugged and forgotten. But almost 20 years later, drillers on the hunt for fossil fuels confirmed the accidental discovery: hundreds of feet below the arid earth of west Africa lies an abundance of naturally occurring, or “white”, hydrogen.

Today, it is used to generate green electricity for Bourakébougou’s homes and shops. But geologists believe that untapped reservoirs of white hydrogen in the US, Australia and parts of Europe have the potential to provide the world with clean energy on a far greater scale.

Arctic spring is getting more erratic

Changing seasons |

|

The timing of spring in the Arctic has become more and more erratic in the past 25 years, leading to growing discrepancies between the behaviour of animals and plants and the conditions they depend on. Since 1996, Niels Schmidt at Aarhus University in Denmark and his colleagues have been monitoring the ecosystem at Zackenberg, a mountain in north-east Greenland. When they analysed the first 10 years of data, they found that spring was arriving around two weeks earlier in 2005 compared with 1996. But now that trend has been replaced by extreme variability from year to year, with animals and flowers emerging at different times. |

The rising cost of net zero

The world’s green energy transition, which is essential to achieving net-zero emissions and halting climate change, is under threat, as a financial era of rising interest rates has made some projects, like new offshore wind farms, unaffordable.

Estimates suggest that Europe must now find an additional €163 billion to reach net-zero by 2050, with figures likely to be similar elsewhere in the world. As such, firms are pulling back from new projects.

Last week, Swedish energy firm Vattenfall announced it would stop work on an offshore wind farm in the UK’s North Sea, warning development costs for the Norfolk Boreas scheme had increased by 40 per cent due to rising interest rates and supply chain costs.

Rising interest rates have made the green energy transition more expensive.

Locals in this British seaside town could revolutionise green energy – if the government lets them

Voters want climate action but don’t trust politicians to do it. Could projects like a Whitehaven windfarm be the answer?

- Rebecca Willis is professor of energy and climate governance at Lancaster University

The seaside town of Whitehaven, in the north-west of England, found itself at the centre of a political storm in May, when the levelling up, housing and communities secretary, Michael Gove, gave his approval for the UK’s first new deep coal mine in more than 40 years just outside the town.

But Whitehaven may soon be known for more than climate-wrecking coal. That is the ambition of Project Collette, a £3bn proposal for a windfarm off the Cumbrian coast to be part-owned by the local community – instigated by the Green Finance Community Hub in collaboration with the engineering firm Arup and community energy specialists Energy4All – and with the potential to power nearby industry.

If Cumbrians could stand on the sandstone cliffs and look out at wind turbines they owned, and that had provided jobs for local people, that might just build the political support and engagement that is so vital to reaching our climate targets?

READ

energy saving trust

Sustainability strategy

Measure, plan and make carbon reductions across your organisation

Are you measuring your organisation’s greenhouse gas emissions yet? We’re here to help if you’re ready to start.

Sustainability strategy

Climate change and your contribution to a better future

This firm is committed to advising clients on better outcomes for the planet. As an example, 20% of funds that we advise on are alternative energy investments.

Our clients, with millions invested in clean energy, are making a real contribution.

Some other funds we support:

– Developing better engineering solutions, such as medical devices and prosthetic limbs.

– Technology that saves energy by stopping the cold escaping from freezer cabinets in supermarkets. Software solutions to manage risk.

– Financing childcare facilities, GP practices ambulances and better care homes.

Britain claims to be at the forefront of the fight against climate change and our scientists and engineers are trusted to provide solutions; your savings and pension pots can make a difference for your children and grandchildren.

Alternative Energy – facts.

The sector offers a range of funds to either provide capital growth, by investing in new developments, windfarms, solar, hydro, anaerobic digestion. Or income generated by buying into long term income contracts, usually 30 years.

Examples of Alternate Energy investments;

One provides money to build has returned 84.17% since its launch in June 2019

The other is an income fund gaining profit from long term energy contracts and returned 101,92% since December 2017.

NOTE: These are no guarantee of future returns

Coal and gas generation is increasing in cost

whilst solar is substantially cheaper.

The economic argument for solar is strong.

For global warming issues . . . surely we want people to stop flying and travelling abroad to enjoy Britain’s own holiday spots?

For our economies, we want more people to spend on UK holidays – including Wales?

So why . . . https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-62956842

Tourism tax in Wales: Levy could apply to Welsh holidaying in Wales

By Brendon Williams BBC News

Visitors booking stays in Wales could face a tourism tax, including those who already live in Wales, the Welsh government has said.

Why are such important and valuable issues ignored by government

Green home upgrades could also create 140,000 new jobs by 2030, analysis by Cambridge Econometric finds

Insulating homes in Britain and installing heat pumps could benefit the economy by £7bn a year and create 140,000 new jobs by 2030, research has found.

But the uptake of these energy-saving measures depends heavily on government policy, according to analysis by Cambridge Econometrics, commissioned by Greenpeace.

Read more … https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/sep/20/energy-saving-measures-could-boost-uk-economy-by-7bn-a-year-study-says

Indigenous leaders urge businesses and banks to stop supporting deforestation

Amazon ecosystem is on verge of collapse, leaders tell brands such as Apple and Tesla as UN gathers in New York

Indigenous leaders from the Amazon have implored major western brands and banks to stop supporting the ongoing destruction of the vital rainforest through mining, oil drilling and logging, warning that the ecosystem is on the brink of a disastrous collapse.

Representatives of Indigenous peoples from across the Amazon region have descended upon New York this week to press governments and businesses, gathered in the city for climate and United Nations gatherings, to stem the flow of finance to activities that are polluting and deforesting large areas of the rainforest.

Biotech firm electrocutes soil so that bacteria can eat ‘forever chemicals’

A biotech firm is trialling the removal of PFAS “forever chemicals” from soil at a test site in Wisconsin by injecting chemical-eating bacteria and electrocuting the ground.

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are a class of thousands of different synthetic chemicals that contain carbon and fluorine atoms linked by strong bonds. The chemicals – which repel grease and water – have been in widespread use since the 1940s in everything from firefighting foam at airports to dental floss.

But the same qualities that make PFAS useful stop the chemicals from degrading, so many of them are persistent environmental contaminants. They are often called forever chemicals, and have been found in drinking water and in people’s blood all over the world.

UK mushroom growing uses 100,000 m³ of peat a year – can we do better?

Peat bogs are an important carbon store, so mushroom growers are searching for a way to grow their produce on other substrates

In a huge industrial shed on Leckford Estate, a farm owned by the supermarket Waitrose in a beautiful part of southern England, a revolution is stirring in the world of mushroom growing. UK production of this crop relies on peat, the incredibly carbon-rich organic matter found in bogs and fens across the country. Peatland contains so much carbon, it is sometimes described as “the UK’s rainforests”.

That is why the UK government has promised to restore 280,000 hectares of peatland in England alone by 2050, to help meet its climate change goals.

How much do food miles matter; should you buy local produce?

Despite a study claiming that food-mile emissions are higher than previously thought, eating less animal produce remains much more important than how far your food travels

Eat locally to reduce food miles and your carbon footprint. That is the message promoted by some environmentalists and businesses, but it has long been clear that often this isn’t true – foods that travel thousands of kilometres can have a lower carbon footprint than local produce.

At least, that is what many studies have found. But research published today in the journal Nature Food claims that global food miles account for 20 per cent of food-related emissions – a much higher proportion than reported in earlier work. So do food miles matter more than we thought? Spoiler: no, they don’t.

The production of the food we eat is responsible for more than a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, so reducing food-related emissions is crucial to limiting further global heating. The question is, what should consumers do to help reduce these emissions?

Previous studies have found that the emissions from food miles – the distance that food has to be transported from where it is produced to where it is eaten, measured in kilometres travelled multiplied by the tonnage – are tiny compared with those from growing that food.

Emissions can be calculated based on how the food is transported – by air or by sea, for instance. A study of US diets by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania concluded that transporting food from farms to shops produces just 4 per cent of food-related emissions, while a 2018 study of European diets put it at 6 per cent.

What this means is that if you want to reduce the carbon footprint of your diet, you should focus on buying foods with lower overall carbon footprints rather than those that don’t have to travel far. This basically means eating less meat and dairy.

For instance, producing 1 kilogram of beef can emit as much as 99 kg of carbon dioxide or equivalents, and making a kilogram of cheese emits up to 24 kg, compared with 0.9 kg for bananas and 0.4 kg for apples.

In other words, what you eat matters to a far greater extent than where it comes from. What’s more, even with the same food types, local isn’t always better. For instance, if you live in a nation with a cooler climate where tomatoes can be grown only using heated greenhouses, these local tomatoes will typically have a higher carbon footprint than those shipped in from a warmer country where no heating is needed.

The latest study doesn’t overturn any of this. For starters, the main reason why it concludes that food miles account for such a high proportion of food-related emissions is that the 20 per cent figure includes all the transport involved, including that of fertilisers, farm equipment and pesticides, not just the transport of food.

“Our study looks at the entire supply chain for food consumption, and naturally non-food commodities are part of it,” says team member Mengyu Li at the University of Sydney in Australia.

It is worthwhile to estimate this, but the team should use a term other than “food miles” to avoid confusion, rather than redefining the existing term, says Hannah Ritchie at the University of Oxford, who is head of research at Our World in Data.

If the standard definition were applied to the numbers in the study, food miles would account for only 9 per cent of food-related emissions, says Ritchie. That is much closer to previous research, though she thinks it is still an overestimate.

What’s more, the study itself calculates that even if it were possible to produce all food in the countries where it is eaten, food-related emissions would fall by only 1.7 per cent overall. This is because although food wouldn’t travel as far, more of it would be transported by road instead of sea, says Li, and trucks produce higher emissions per tonne of cargo than ships.

“So, overall, the bottom line is still that what you eat has a much bigger impact on emissions than the distance that food has to travel to reach you,” says Ritchie.